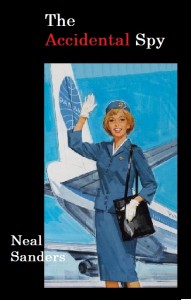

The Accidental Spy

If you are looking for the ‘Reader’s Guide’ to The Accidental Spy, click here.

To order the book from Amazon.com, click here.

Genesis of The Accidental Spy

The thing that gets drummed into you in every writing seminar is the four-word mantra, ‘write what you know’.

The thing that gets drummed into you in every writing seminar is the four-word mantra, ‘write what you know’.

When I started cataloging the things I knew about, the list contained some oddities that aren’t in every writer’s bag of tricks. For one, I grew up in an airline family and lived in an airline community and absorbed the lore of that industry in my formative years. Second, I worked in high technology virtually all of my adult life and am very familiar with the history of semiconductor technology. Third, I came of age in the 1960s in Miami and have a fairly good memory. And, for what I mis-remembered, there’s always the internet.

The history of the semiconductor industry is not an especially linear one with bright lines defining key players and events. Sure, everyone knows Intel introduced the 4004 microprocessor in 1971, but what came before it? Could someone have invented something almost as good a few years earlier? And, if they did, what would it be worth?

Throw in those elements, add a dash of romance, mix well, and the result was a story that was a pleasure to write.

If you haven’t bought The Accidental Spy, please be my guest and enjoy the first two chapters below. If you’ve purchased the book either in print or as an e-book and want the ‘Reader’s Guide’ to it, click here.

The Story in Brief

Meet Susan Delaney. It’s 1967 and, until now, the extent of this 27-year-old stewardess’ ambition was working her way up to serving first class on Pan Am’s New York – Paris run, and meeting ‘Mister Right’. Then one day, she accepts an offer to escort a misplaced bag to its owner in Miami. The next thing Susan knows, she’s part of a cross-country chase that pits the CIA, Mossad, the Mafia, and the KGB against one another.

Susan’s life will depend upon her two allies: Joe, a Mossad agent with a Paul Newman face and a mischievous smile, and Sadie, a grandmotherly El-Al air marshal whose knitting bag contains a lot more than balls of yarn.

The stakes couldn’t be higher: the suitcase Susan escorted contains what may be the plans for and samples of the first microprocessor – a design that everyone who sees it wants to own or, better yet, to steal. No one knows the microchip’s origin, but the engineers who see it recognize it as the real thing.

As readers, we know one more critical thing: that in 2011, there’s a body buried in Susan’s back yard and that it has been there since the events of the book. What we don’t know is whose body it is.

Susan’s unwitting entanglement will take her to San Francisco during the Summer of Love, New York, Washington, and a South Beach that far predates the arrival of the Beautiful People. Along the way, she’ll have to deal with a shadowy anti-Castro group, a legendary mob boss and spies of many nationalities. She’ll also see the dawn of the microelectronics industry and the Cold War up close. And Joe just might be Mister Right.

THE ACCIDENTAL SPY

1.

Susan Delaney sat in the only comfortable chair in the construction trailer. A rattling window air conditioner blasted a chilled, dehumidified breeze over her body; a marked contrast to the ninety-degree, water-saturated air outside. On the work table before her were inch-thick piles of building plans. Hung from the wall was a framed artist’s rendering of the planned finished product some two years hence: twin concrete and glass condominium towers with the utilitarian names ‘Biscayne Vista I’ and ‘Biscayne Vista II’.

Through the window over the work table, Susan could view the construction site. It was a barren expanse of crushed oolite, coquina rock and sand; the original fill put there a hundred years earlier by Carl Fisher, who had purchased a boggy, mosquito-infested barrier island and envisioned Miami Beach.

Until a month ago, her home had stood on this site on Purdy Avenue. She had sold it a year earlier to an earnest New York couple who had spoken of moving to Miami Beach for their retirement while using it as a weekend home. While they had been anxious to close, which concerned her, they had offered her up to a year to live there while looking for a new home, which she had ultimately found in the mountains of North Carolina.

For ten years, Susan had ignored the unwanted and unsolicited, escalating offers for her property, all the while watching the inexorable march of high rises moving up the western shore of Miami Beach. She had thought this stretch of Purdy Avenue was safe. Her neighbors shared her antipathy for what they derided as tacky condo developments. They had all vowed they would never sell to developers; that there would continue to be bayfront, single-family homes in southern Miami Beach.

Clearly, her neighbors had changed their minds. Her home was gone as were three adjoining properties. The result was a 50,000 square-foot parcel with 300 feet of frontage on Biscayne Bay. The New York couple had likely fronted for a developer all along, wooing her even as her neighbors were wooed by other shills. Each had probably thought their cherished home was safe for another generation. Within six months, each had been flipped and the developable parcel assembled. Now, there was only a flat expanse of white rock, marked with wooden stakes bearing strips of red plastic where concrete footings would be driven a hundred feet into the limestone below to anchor the condominium towers.

One element marred the flotilla of waving red plastic strips: a neat rectangle of wooden stakes with continuous band of yellow tape imprinted ‘crime scene – do not cross’.

Before her in the trailer, standing impatiently, was Detective Ramon Suarez of the Miami Beach Police Department. Detective Suarez had been fidgeting for some minutes. Based on years of professional observations, Susan surmised that he badly craved a cigarette. But, until he had her statement, there could be no nicotine fix.

“We need to talk about the grave, Ms. Delaney.”

It was his third effort to get the conversation started. Susan was not yet ready to begin talking. The call from the police department had come two days earlier, inquiring if she had been the owner of a home located at 1912 Purdy Avenue. As soon as she heard who was asking the question, she knew exactly why it was being asked.

And she had known that the question was inevitable from the moment she had heard of the re-sale of her home by that New York couple. She ought not to have sold. She ought to lived in the home for the rest of her life. But she had deluded herself into thinking that Dr. and Mrs. Abernathy were sincere when they said that they wanted a single-family home on Miami Beach and not a look-alike boxy condo. They had walked her lush garden with its hibiscus, crotons, allamanda and bougainvillea and vowed to preserve what she had created. They had listened carefully and made written notes when she pointed out where coconut palms had once stood but had been cut down in the 1970s because of the blight. The Abernathys made her comfortable, and now she was paying for that false sense of security.

She had thought of the questions that would be asked and of the answers she must give. An answer of, “I have no idea of what you’re talking about” would be greeted with suspicion and more investigation. Inevitably, the story would have been pieced together. On the flight down she had pondered other courses of action: fleeing to South America or disappearing from a cruise ship at some obscure port of call. Once upon a time that might have been possible. Now, it was not.

The police had been kind. She had been invited to give a voluntary statement at a time and place of her choosing, and Detective Suarez had volunteered to fly up to North Carolina. No, she had told them, if there was a statement to be given, it should be in Miami Beach and, preferably, at the site of her home.

Make it soon, she had been told. Construction had been stopped because of the discovery of the grave. It could not be resumed until sufficient answers had been obtained.

That’s fine with me, she had thought. “I shall be down as soon as I can make arrangements,” is what she had said.

And so now, two days later, she was in this construction trailer outside of the place she had called home for more than fifty years.

“How old are you, Detective Suarez?” she asked.

The question took him by surprise, but he was quick to answer. “Forty-two,” he said.

“You were born in 1969,” she said. “And how long have you lived in Miami?”

“Thirty-one years,” he said. “And, while it doesn’t make much of a difference, I was born in 1968. I’ll be forty-three next month.”

Susan did the rapid mental arithmetic. A Marielito, she thought. Detective Suarez would have come as a boy to Miami as part of the flotilla of refugees who left from the Cuban port of Mariel in 1980 when Castro had briefly said ‘good riddance’ to the country’s malcontents, as well as to a sizeable percentage of its prison population. “Then what I am going to tell you will be utterly alien to you. It happened before you were born and in a place that, while it has the same name, bears no resemblance to the city with which you are familiar.”

“Yes, ma’am,” Suarez said. She’s finally ready to talk. He regarded Susan Delaney. Remarkably well preserved for someone who, according to his paperwork, was in her early seventies. Silver hair, simple makeup. No absurd dye jobs, no laughable face lifts or Botox regimens. Slender now, so she had likely been fit all her life. She would have been quite a looker in her prime. She was still attractive. Probably had all of the old codgers in the retirement home panting after her, clutching their chests for the effort.

“I will tell you my story and I will tell it my own way and at my own pace,” she said. “You look to me as though you need a cigarette. I suggest you go outside and have two or three now because, once we start, we are likely to be here for awhile.”

Not surprisingly, Detective Suarez took her up on the offer.

While Suarez was outside, Susan Delaney looked again out the window of the construction trailer and at the yellow crime scene tape. She mentally measured the distance from the seawall line to the tape. Yes, about thirty feet. There would have been the bib of St. Augustine grass just in front of the cordoned-off zone, the area inside the markers a mass of hibiscus and elephant ear. Next to it would have been the small guest house and a low hedge of ixora and taller crotons, which had replaced the key lime and orange trees that had been felled because of the threat of citrus canker in the 1990s. The north wall of her house would have stood about fifteen feet away, its base lushly planted with crape myrtle and purple bougainvillea.

Now, there was no trace of the vegetation or of the house. Everything had been scraped clean and carted away. Only the smoothly graded, ground-up coral and limestone remained.

And the grave.

Outside the construction trailer, Detective Suarez consumed a second cigarette. He loosened his tie and shielded his eyes against the glare of the crushed rock. He, too, looked at the area flagged with the crime scene tape. It wasn’t much of a grave. One skeleton, wrapped in a shower curtain. The ME said it had been there since the sixties. The goddam body has been in the ground for more than forty years, Suarez, his lieutenant had told him. These guys are leaning on everyone they know in city hall and pulling every string they can to get us out of here. They’ve got fifty grand a day of payroll and interest payments, and all they want to do is start driving piles. So just get her statement. We’ll sort out the charges later.

Suarez crushed the second cigarette with his foot. At fifty thousand dollars a day, he figured his five-minute cigarette break had cost the construction company about three hundred and fifty dollars; about what he made per day as a Miami Beach detective. Fair exchange.

He went back inside the trailer.

Susan Delaney had shifted position. The chair now faced toward him. She had relaxed, her body showed comfort where, before, it had showed stress. She looked at him to determine if he was ready to listen.

“In July 1967, I was twenty-seven years old,” she began. “I was single, and I was making my own way in the world to the extent that women were allowed to do such things. My father had founded a tool-making business in Cleveland, and the Second World War had made him a moderately wealthy man. In 1948, he announced that Shaker Heights was ‘too damn cold in the winter’ and he packed us off on a train to Miami. He disliked hotels, and in just over a week after our arrival that first year, he acquired 1912 Purdy Avenue. Thereafter, my parents spent four months a year at the house. Being in school, I came down for Christmas and New Years.”

“I graduated from high school in 1957. I had no career aspirations, but neither did I wish to spend my days in the perpetual company of my mother. And so I enrolled, somewhat to my surprise and definitely to the astonishment of my parents, at the University of Miami. But it was, after all, 1957, and women studied things appropriate to their sex. I majored in Sociology and minored in French. At the end of four years, I was qualified to do one thing: marry a doctor and be a scintillating hostess for his dinner parties.”

“While I had dated a number of medical students, there were none I felt compelled to marry. Today, not being interested in getting married after college may sound rather ordinary. But in 1961, the average age at which a woman married was nineteen. I was, in the eyes of my parents, already two years past my prime. They had, after all, agreed to pay for college principally because they rather looked forward to having a doctor in the family.”

“And so, armed with a degree that was of absolutely no value from a college that was, to say the least, academically suspect, I combed the ‘help wanted – female’ advertisements. It took only two weeks for me to discover that I had neither the desire nor the fortitude to become a secretary, receptionist, waitress, or department store clerk. I wanted adventure. I wanted freedom. In short, while it had never crossed my mind while I was in school, I wanted to be a stewardess. More specifically, I wanted to be a Pan American stewardess.”

“Pan Am wanted only cosmopolitan, multilingual university graduates. They wanted me. My second graduation, and to me, the one that counted, was in January 1962. I had my wings, a very smart uniform and a paycheck. What’s more, I was based in Miami. I had, during my college years, come to look at the house on Purdy Avenue as my true home. And, while I would have accepted a posting in New York or Paris, I was beginning to think of myself as a Floridian.”

“I could not have been happier. For the next five years, I flew the world. I worked my way up the route structure. I had found my calling. Yes, by 1967, when I was twenty-seven years old, I was where I wanted to be. I was single, reasonably attractive, and I was making my own way in the world.”

Susan paused and looked the detective squarely on. “Now that you understand that, I can tell you about the body. It was a murder, and a particularly cold-blooded one. It took place on July 25, 1967 and I know the exact circumstances of that murder because I was an eyewitness to the event. I know who the victim was and I know who committed the crime.”

“Do you need another cigarette, or may we begin?” she asked.

Detective Ramon Suarez shook his head vigorously. “The floor is yours, Ms. Delaney.”

2.

It started with a suitcase. Your basic gray, American Tourister overnighter. Not the huge, three-suiter than your Aunt Wilma packs when she comes to visit. Rather, the smaller one that holds a change of clothes and some toiletries. Every third person who gets on an airplane checks one through. When you get to your destination there’s an easy drill: you go to baggage claim, you look at all of the other gray suitcases, and you pull out the one that matches your claim check. You hold the two numbers side by side to verify that they match. You show your claim check to the guy by the door and he matches numbers. Then he waves you through. Nothing could be easier.

Except that somebody in too big of a hurry got off Pan Am’s Stockholm – New York flight, cleared immigration, and grabbed the wrong bag. And the guy by the baggage door didn’t look closely at the numbers because he was probably too busy trying to make time with one of the Hertz ladies. And then the schnook hops on a flight to Miami and gets all the way to his hotel before he figured out he had the wrong bag and he probably doesn’t have a bathing suit. So he calls New York baggage ops and starts screaming that he needs his bag.

I had worked the Paris to New York run – economy class, of course – and was looking forward to four days off, but not before I did some serious flirting with Charlie. Charlie is Pan Am’s baggage supervisor at Kennedy, and he and I had been making eyes at one another for the better part of six months. The word on Charlie was that he was management material and that Juan Trippe was personally guiding his career, and that a stint in baggage ops was the last step on the road from the WorldPort to the headquarters building on Park Avenue. I didn’t especially know if I wanted to become Mrs. Charlie, I just thought he was cute in a Tony Curtis kind of way and was interested in knowing if he danced as good as he looked.

But Charlie was distracted, or at least he was distracted until he saw me sashaying toward his office.

“Susan, you’re just the person I’m looking for,” he said.

“Is that an invitation to dinner?” I asked. Visions of The Four Seasons appeared in my head. Maybe dancing afterward. I could always get a later flight. The planes to Miami fly empty in July.

He paused. Not the question he had expected. Maybe he wasn’t management material after all. “Not… exactly,” he said. “Are you headed home this afternoon?”

I nodded. Not the question I expected, either. But then I knew I wasn’t management material. Not that anyone would have hired a woman as an executive.

“Would you like to make fifty bucks?” he asked.

Fifty bucks was half of a week’s take-home pay. Of course, stewardesses aren’t in it for the pay. While your take-home pay might be just a hundred dollars a week, you might run up three times that amount in living expenses on a Paris or Rome layover, with the airline graciously footing one hundred percent of the bill. But fifty bucks in cash would pay my taxi home from Miami International Airport, fill my car with gas, put three bags of groceries in my refrigerator, and pay the electric bill.

“Sure,” I said, good-naturedly. So much for flirting. So much for dinner and dancing.

He walked over to a small, gray American Tourister bag. “This bag needs to get to the Fontainebleau Hotel tonight. This guy flew in from Stockholm and was connecting to Miami. He’s begging for the bag. He’s called five times. I can give you fifty bucks to escort the bag to Miami, chances are he’ll match it on his end.” He looked at me hopefully, with those Tony Curtis eyes. “Give him this bag. Retrieve the bag he grabbed by mistake, give that one to the concierge at the Fontainebleau. I’ll have the van pick it up in the morning. Deal?”

“Deal,” I said, a little wistfully. Sayonara dinner and dancing at the Four Seasons. But hello fifty bucks and solvency.

An hour later I was on a southbound National Airlines flight. First class, because there were maybe fifteen people on board. Florida in July. Right. I spent the flight gabbing with the National stews with their three-year-old Oleg Cassisi outfits, protesting that National was right up there with Pan Am in respectability, which we all knew was a crock, but sounded good coming from someone in a brand new sky blue Halston uniform and perky hat.

I collected the errant bag in Miami together with the rest of my luggage – the guy at the door actually spent about ten seconds making sure the claim checks matched – walked out the baggage claim door and into a steamy Miami evening. I raised my hand and a Yellow Cab rocketed into place in front of me. I threw my bags into the back seat and got in.

“The Fontainebleau,” I said.

The cabbie looked in the rear-view mirror and shook his head. “Pan Am doesn’t put up crew at the Fontainebleau. You must want…”

“I’m dropping off a bag as a favor,” I interrupted. “Then, you’re taking me home.”

“Got it.” The cab accelerated away from the loading zone so fast it made my head snap.

The cabbie made it to the hotel in twenty minutes by using an impressive display of driving skills that included inching the speedometer over eighty as we crested the Julia Tuttle Causeway and forcing a VW Beetle onto the sidewalk on Collins Avenue. This was a driver whose true calling was Indianapolis on Memorial Day weekend.

The meter showed just under $11 and I asked him to wait five minutes while I delivered the bag. “I live about two miles away,” I said. No reason to pay another throw charge, plus there wasn’t another cab in the hotel portico. July in Miami. You want a cab? You call one. Or you take the bus.

The slip of paper Charlie had given me said Peter Johanssen was in room 712. I got on the elevator with the suitcase and practiced my smile. I was hoping Peter was good for at least twenty bucks, and I was prepared to shake my tush if it got me the fifty Charlie has intimated was possible.

The elevator door opened on seven and I turned right. Johanssen’s room was three down and the door was open a crack. I knocked.

No response.

“Mr. Johanssen?” I called out.

Still no response.

So I pushed open the door a few inches and peeked inside.

The place was a mess. Every drawer pulled out, the bed off of its frame and the mattress in tatters. Three suitcases were on the mattress bottom, open and empty with their lining ripped out, one of them a perfect match for the bag I held in my hand. No sign of Mr. Johanssen but the sliding door was open onto the balcony.

I didn’t go inside the room – I’m not that stupid.

Instead, I walked to the end of the corridor and went into the stairwell. I walked down four flights and then went back to the elevator bank. Thirty seconds later, the elevator door opened on the lobby level to the sound of shouts and people running toward the pool and the ocean beyond.

I didn’t follow them – I’m not that stupid, either.

I heard several ‘Oh, my God’- type gasps and my mind filled in the image of Mr. Johanssen face down on the terrazzo after a fall of seventy feet. It couldn’t have been a very pretty sight and I’m not very good around blood, my first-aid training notwithstanding.

I walked slowly toward the front entrance. The bellman that would have been there to open the door was part of the crowd out back looking at Mr. Johanssen.

But a man was there. He was in a dark suit and tie and wore a hat, which put him definitely out of place in the Fontainebleau. I gave him my brightest smile. I walked the few feet to the cab. The driver was standing by his cab. He saw me and opened the door.

It was the first time I had seen my cab driver’s face. Think Paul Newman. Late twenties, a face with a smile that melted your heart. A rugged face with no baby fat. Dark brown curly hair. Beautiful blue eyes that crinkled around the edges and promised a little mischief. A nose that looked like it had been in a few fights, but fights that he had won decisively. And a lean, Paul Newman body, slouching by the taxi like in Harper until he saw me coming out the door.

“I’ll keep this in the back seat,” I said and got into the cab.

The driver closed my door and went to the driver’s door. He got inside and turned around. “Everything OK in there? Sounds like a lot of commotion.”

“Just pull out of the hotel,” I said. “Please, let’s go. Now.”

We cleared the hotel entrance and were on Collins Avenue.

“Pull into the next driveway,” I said. He did so.

“Now, there was a man by the hotel entrance in a suit,” I said. “He wasn’t there when I went in. When did he show up?”

The cabbie nodded. “You went up one elevator, he came down another about ninety seconds after you went up. Three guys, all in suits and hats. One pointed at the front entrance and the guy you saw stationed himself there. The other two went right.”

“Did the guy by the door keep watching me after I went out the door?”

“Yeah, but he was, ummm, watching the way you walked. That’s where his eyes were focused.”

I pondered that for a moment. As I did, three police cars came screaming from the north down Collins, sirens blaring. They screeched into the Fontainebleau entrance.

“You want to tell me what happened?” the driver asked.

“Take me home,” I said. “I need some time to think. 1912 Purdy Avenue.”

The driver made a U-turn and started south on Collins. Two more police cars were rushing from the south.

A man flies from Stockholm to New York. He checks though three bags. In New York, he claims his bags but mistakenly picks up the wrong suitcase as one of them. He goes through customs in mid-afternoon at the biggest international port of entry in the country when the place is a circus and he has nothing to declare. The odds are that the bag was never even opened. He goes to the transfer desk and turns over the bags to Eastern or National, collects his new claim checks, and that’s the end of it until he get to Miami and discovers that one of his bags is the wrong one. He calls Pan Am. He calls Pan Am multiple times because this is the important bag. Pan Am baggage says they’ll get the bag to him on the next available flight. I walk into the baggage office.

In the meantime, someone else is looking for Peter Johanssen and they find him at the Fontainebleau. They ransack his room and, when they can’t find the suitcase, they question Mr. Johanssen. When they were done questioning him, they dropped him over the railing of his balcony…

The driver was threading his way across Miami Beach when he came to a red light and said, “And I’m guessing that all those police cars have something to do with the person you were going to see.”

I was startled and sat up straight in the back seat. “Why do you say that?”

He looked at me in the rear view mirror and I saw the crinkle around his eyes. “You’re sitting back there, thinking. I’m up here, thinking, too. You said you were dropping off that bag as a favor. You went into the hotel with it. You can out of the hotel with it less than five minutes later. I know it’s the same bag because it still has the ‘Crew’ tag on it. Something happened in that hotel right about the time you went into that elevator. When you come back down, there are three guys who definitely aren’t here on vacation looking for someone or something.”

He paused a moment. Looking to see if he had my attention. He did. “I’ll bet you that if you were going into the Fontainebleau a couple of minutes later, they would have stopped you. But you were going out, plus you’re a stewardess. It’s going to take them a while to figure out that the suitcase walked right by them and all they did was watch the way you put one leg in front of another.”

“Who are you, James Bond?” I asked, incredulous that he could have been so observant.

“No, it’s Joe Klein. But I spent a couple of years in the army keeping an eye on guys like those goombahs in the lobby. If there’s one thing I know, it’s how people behave when they’re set up to surprise and intercept someone. But I’m betting they’re not the brightest bulbs in the chandelier. You threw them a curve ball by walking out when they were primed to look for someone walking in. But sometime later tonight, they’re going to put their heads together and they’re going to remember that the only person with the right kind of suitcase was a blonde stewardess and that she got into a Yellow Cab.”

“What I’m wondering is if that guy by the door made note of my license plate,” Klein said. “I’m hoping he didn’t or, that by the time they debrief one another, all he’s going to remember is ‘Yellow Cab’.”

I was absorbing his brilliant line of observation when he asked, “So, what’s in the suitcase?”

“I have no idea,” I said. “I’m just doing a favor for baggage services in New York.”

We were in front of my house.

He put the can in park and turned off the engine. He turned around to look at me, crossing his arms across the seat and resting his face on his arms. “So do you want to have a look?” he asked.

I pondered that question for a moment. I really didn’t want to be alone while I figured out what I should do. But I’m also smart enough not to invite strangers into my home.

“Look,” he said, “If they’re smarter than I give them credit for, they’re going to start looking for Yellow Cabs, calling dispatchers, and telling sob stories about leaving something small and precious in the back seat. And my dispatcher is dumb enough to fall for that kind of line. If I’m going to get beat up by a bunch of goons looking for your suitcase – and, by the way, I won’t tell them where you live, no matter what – I ought to at least be entitled to know what the fuss was all about.”

And then he flashed a genuine Paul Newman smile. “And besides, I could use something cold to drink.”

Call me a sucker for a pretty face. That was all the push I needed.

“Let’s go inside,” I said.